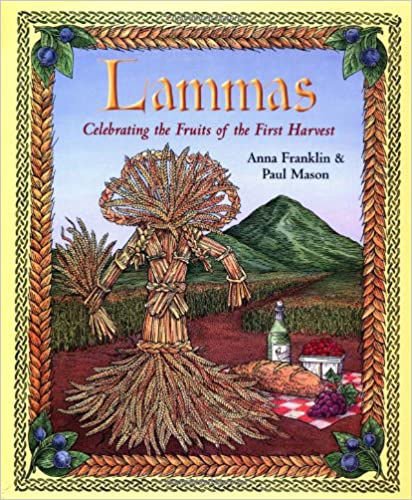

Lammas

Lughnasa is also called Lammas, from the Anglo-Saxon hlaef-niass, meaning “loaf-mass.” The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of 921 CE. mentions it as “the feast of first fruits,” as does the Red Book of Derby. It was a popular ceremony during the Middle Ages but died out after the Reformation, though the custom is being revived in places. It marks the first harvest, when the first grain is gathered in, ground in a mill, and baked into a loaf. This first loaf was offered up as part of the Christian Eucharist ritual.

There was a Lamb’s Mass held at the cathedral of St. Peter in York for feudal tenants, and some say this may have given rise to the name since fresh baked bread and lamb are traditionally eaten at Lammas. This seems unlikely. Since Lammas was celebrated only in Britain—no other Germanic or Nordic peoples observed Lammas or held any other feasts on August 1 — it seems more likely that it was merely a renaming of the Celtic Lughnasa. (However, important festivals were celebrated elsewhere around this time, and these throw new light on the meaning of Lughnasa.)